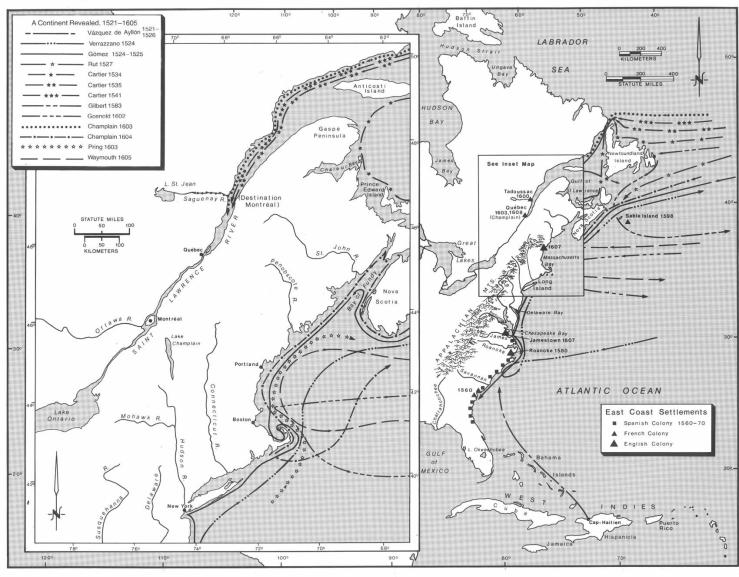

In January 1524, Giovanni da Verrazano and crew set sail from Madeira, the Portuguese island off the northwest coast of Africa, and later made landfall at what was probably Cape Fear, North Carolina.

Their ship, the Dauphine, tacked northward to avoid Spanish settlements to the south. At some point before July, they dropped anchor in New York Harbor. Verrazzano’s account of his trip includes the first known description by a European of what is today New York Harbor and New Jersey and their inhabitants:

“After a hundred leagues we found a very agreeable place between two small but prominent hills; between them a very wide river, deep at its mouth, flowed out into the sea; and with the help of the tide, which rises eight feet, any laden ship could have passed from the sea into the river estuary [the Hudson].

Since we were anchored off the coast and well sheltered, we did not want to run any risks without knowing anything about the river mouth. So we took the small boat up this river to land which we found densely populated. The people were almost the same as the others [encountered at points south], dressed in birds’ feathers of various colors, and they came toward us joyfully, uttering loud cries of wonderment, and showing us the safest place to beach the boat.

We went up this river for about half a league, where we saw that it formed a beautiful lake, about three leagues in circumference. About XXX [30] of their small boats ran to and fro across the lake with innumerable people aboard who were crossing from one side to the other to see us…”

(Verrazzano, Giovanni da. “Translation of the Cèllere Codex (Chapter 9).” In The Voyages of Giovanni Da Verrazzano, 1524-1528, edited by Lawrence C. Wroth, translated by Susan Tarrow, 133ff. New Haven: Pierpont Morgan Library by Yale University Press, 1970.)

Verrazzano was an Italian navigator who undertook three voyages to the New World. The 1524 expedition was the basis for French claims to empire in the Americas.

After his return to Europe, Verrazzano wrote a letter to King Francis I of France, who had sponsored the voyage, from which the quotes above and below are drawn. A copy of this letter surfaced in 1908 and was purchased by the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York shortly after. It is known as the Cèllere Codex, and a scholarly translation from the original Italian to English, available by creating a free account with the Internet Archive, was published in 1970. A version intended to be assigned to students, with notations about location, is here. (A list of primary documents for North American colonial history, complied by the National Humanities Center, is here.)

Verrazzano’s very first impression was of a “new land which had never been seen before by any man, either ancient or modern. At first it appeared to be rather low-lying; having approached to within a quarter of a league, we realized that it was inhabited, for huge fires had been built on the seashore”.

Throughout the narrative, Verrazzano remarks on the abundance of nature. He describes unfamiliar plants and animals, and at a number of points remarks on the density of the indigenous population. The latter is open to interpretation because Verrazzano also seems to have thought that he had arrived in Cathay (China).

The interactions with native groups that Verrazzano describes are relatively peaceful with two notable exceptions. The Europeans kidnap a young boy over the vigorous protests of female relatives, probably including his mother. Toward the end of the voyage, an indigenous group Verrazzano encounters near Cape Cod, when it becomes obvious that the Europeans have no more gifts to give, turns mocking in a comic episode that presages future hostility:

If we wanted to trade with them for some of their things, they would come to the seashore on some rocks where the breakers were most violent, while we remained in the little boat, and they sent us what they want to give on a rope, continually shouting to us not to approach the land; they gave us the barter quickly, and would take in exchange only knives, hooks for fishing, and sharp metal. We found no courtesy in them, and when we had nothing more to exchange and left them, the men made all the signs of scorn and shame that any brute creature would make [such as showing their buttocks and laughing]. Against their wishes, we penetrated two or three leagues inland with XXV armed men, and when we disembarked on the shore they shot at us with their bows and uttered loud cries before fleeing into the wood…”

Brackets in paragraph above indicate marginal notations in the Codex. See Humanities Center version.

On his third voyage to the New World, Verrazzano, according to one story, was “captured, killed, and eaten by cannibals” in the Lesser Antilles. Whether this is true, the account of Verrazzano’s first encounter with the Americas has an element of wonder and drama, and intimations of violence, characteristic of other first encounter narratives.

The narratives of these early Italian, French, and Spanish inhabitants of North America, including along the East Coast, deserve to be more widely read and understood in U.S. classrooms, particularly for their very earliest descriptions of original peoples.